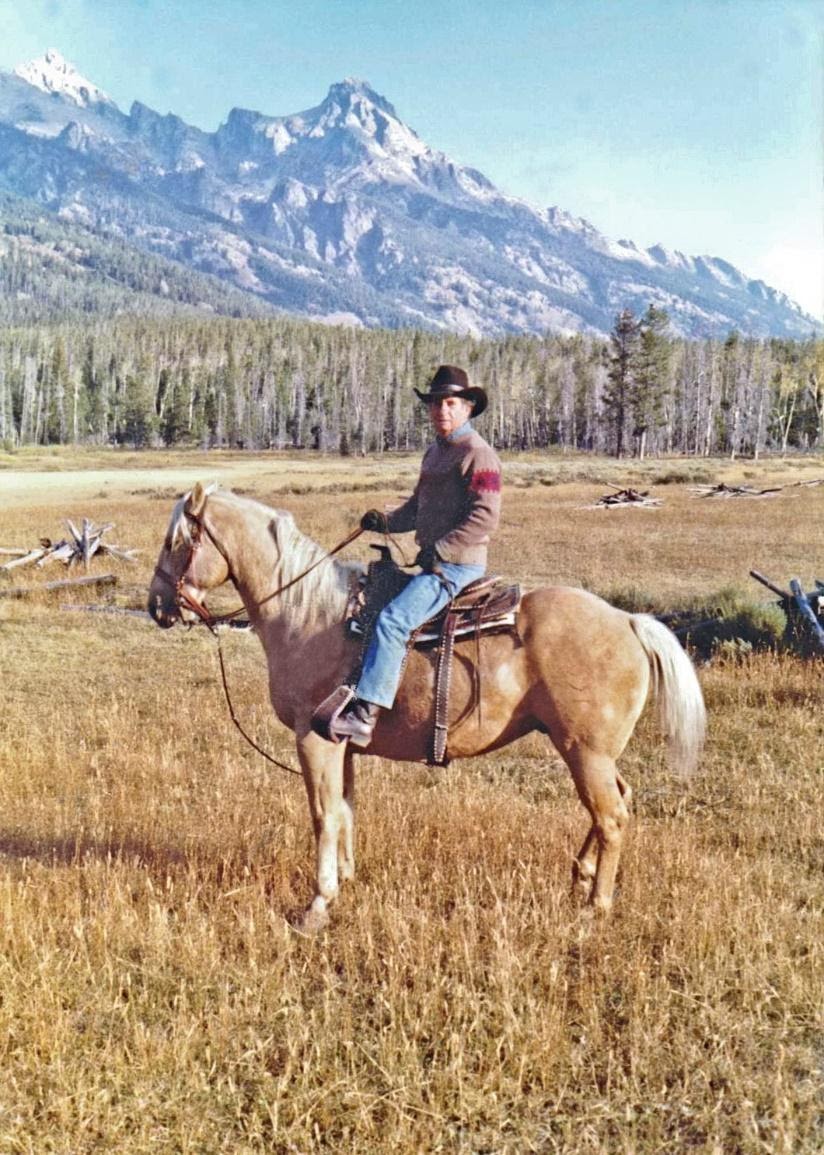

I remember my father’s last and best trail horse, Scout. He was a big, bold, grade quarter horse, afraid of nothing, with a motor like a freight train. Aboard Scout, my father climbed all over the mountains surrounding Jackson Hole, Wyoming, usually ponying a string of pack horses. He always said, “Julie, you could ride a well-trained horse over a cliff if you wanted to, because he’ll go anywhere you point him without argument.” He also said Scout would sleep in his bedroom, if only he could figure out how to get him down the hallway.

I was fortunate to climb some of those Wyoming mountains with my dad, horse packing point-to-point in some of the most magnificent terrain in the country. My dad was always up for an adventure—you could count on every outing entailing surprise. There wasn’t much terrain he would shy away from, and Wyoming has a lot of rugged mountains!

But my perspective on great trail horses involves more than the adventures with my father. I first moved to Colorado in 1984, fresh out of college, and promptly landed a job guiding hourly trail rides in the Sangre de Cristo mountains and wrangling dude horses for an outfitter. The Sangres are notoriously steep and wild. It’s not a popular area for riding horses, and I have come to understand why.

Despite the wild terrain, we took people who had never ridden a horse before all the way up to the tree line. In a way, it was better that way because they were unaware of all the things that could go wrong. “Just lay the reins over the horn, hold on with both hands, and don’t move!” The horses would make it safely across the treacherous scree slope with incredible sure-footedness, as long as the rider stayed out of their way. This is where I formed the strong and everlasting opinion that good dude horses are worth their weight in gold.

Being a trail guide and wrangler in the high mountains, sometimes leading three pack mules while keeping an eye on the dudes, shaped my perspective of what it takes to make a great lead horse. To me, a great trail horse is also a good lead horse—your partner in safety, in control, and in, well, leadership. It’s the kind of horse that would jump off the cliff for me, if I asked, but that trusts me enough to know I would never ask him to do anything we couldn’t handle together.

Scout was an exceptional lead horse and pulled my father out of many hairy situations. My old Morgan mare, Pepsea, was too, and I guided trail from her for a couple of decades. She was possibly the best lead horse I’ve ever known. We climbed a lot of mountains together and she was a reliable partner through thick and thin.

I’ve ridden a few other great lead horses over the years—enough to know that my young horse, Pepperoni, has the prerequisites needed, and he may make the cut. Which brings me to the age-old question… is a great horse born or made? Nature vs. Nurture.

The truth is, it’s difficult to answer that question, because from the moment a horse is born his learning begins. A naturally good-tempered horse can turn sour in the wrong hands, and a horse with a challenging temperament can be shaped into something amazing. But starting with the best raw ingredients, then adding copious amounts of training and experience, you can turn an average-performing horse into a great one.

In previous installments on the making of a trail horse, I’ve written about the qualities of a good trail horse, the manners and ground training it needs, and the foundational under-saddle training that will take him from average to exceptional. Now it’s time to talk about the hard stuff.

To Lead or Not to Lead

To be truly exceptional, I think a trail horse must be willing to accept any position in the lineup—in front, in the middle, or at the end. I think he should always mind his manners and rate his speed, keeping appropriately distanced from the other horses. He should be willing to ride calmly away from the herd any time I ask, and be happy going out alone—just the two of us. He needs to act the same way every day so that I can count on him when the going gets tough. He needs a lot of awareness and presence and some sense of caution, but not be prone to flight.

Being exceptional is not easy or common. It’s a very tall order, and not all horses will pass the test. Even with a lot of natural talent, it still takes training and experience, over months and years—not hours and days—to make a good horse great.

The Right Stuff

It’s not hard to train a horse to follow another horse down a trail. That’s completely natural, and they would probably do it on their own if you turned them loose. Horses naturally stay with the herd and follow the leader.

Horses are instinctively drawn to other horses because they are prey animals, and there is safety in numbers. Taking that theory one step further, imagine you’re a horse traveling with your herd through treacherous terrain in lion country (think Sangre de Cristos). Where would you feel safest? Right in the middle of the herd. It’s the horse in front that gets sucked into bogs or falls in the hole; it’s the horse in the back that gets picked off by the lion. For many horses, being out in front or tailing behind is untenable.

Horses can be very social, but also jealous and competitive animals, prone to seeking higher status in the herd. It takes a brave and confident horse to lead, but those qualities often come with dominant personalities. While many horses don’t want to be out front, some insist on it and throw a wall-eyed fit if you try to ride in the middle or tail-end. To me, the best trail horse is the one that likes being out front, is eager to head down the trail and see what’s around the corner, but is happy to let others lead or bring up the rear.

Flight and investigation are also instinctive behaviors of horses, even though they are opposite qualities. A horse “hits the ground” with its temperament and these qualities can become apparent from the moment it’s born. Some horses will be high in flight and low in curiosity; others low in flight and high in curiosity; while some hit right in the middle. It’s obvious that for a good trail horse, you want the latter. But again, be careful what you wish for, because a very brave, bold horse can also be quite dominant, and may be prone to question your authority.

Energy and sensitivity levels are important qualities inherent in the horse’s temperament, and once again, be careful what you wish for. For myself, I know I need a forward-moving and forward-thinking horse, one that is sensitive to his environment and responds to the lightest cue. But there is a very fine line between that and a horse that spooks at his own shadow and spins and bolts like his hair’s on fire.

To be exceptional, the horse must be my partner in all things—be willing to work as hard as I am, to be as achievement-oriented as I am, and to be game for an adventure together. I believe that a good work ethic can be trained into any horse, no matter how lazy, and that a horse with a natural work ethic can be worthless if poorly handled.

Beyond his temperament, that exceptional lead horse must also be strong and athletic to get me out of tricky spots and handle the unexpected. But not so tall that I am ducking under every branch or need to carry a step ladder. And since I don’t ask for much, I’d like him to be smooth gaited, so I can ride all day and my saddle bags aren’t flapping.

The best raw ingredients in the temperament of an exceptional trail horse are willingness, bravery, curiosity, adventurous, independent, steady, reliable, energetic, aware, thinking, and game. These ingredients alone won’t make any horse exceptional. Starting with the right stuff helps, but there’s still a lot of training and shaping yet to come.

Education and Experience

Every successful horse trainer knows that some horses are easier to train than others. Some horses are so willing and eager-to-please that shaping their behavior is easy. Others, not so much. I believe strongly that good training and solid, consistent handling can make any horse a great horse. We can always improve a horse through training, though starting with quality ingredients sure helps.

Some of the qualities of an exceptional trail horse are baked into his temperament, but others come from training and handling from a young age, nurturing the horse along slowly, so that he only develops good habits and never learns behaviors that will affect his ability to do his job later. Ground manners, ground skills (like trailer loading and ground tying), finish training under-saddle, work ethic, and the ability to perform in all settings (independently of the herd), are trained into the horse over time.

In part two of this series, I talked at length about manners and ground skills that are important for a good trail horse, but to be an exceptional trail horse there must be more. Over time, with consistency and experience, the exceptional trail horse learns his job and understands his role. He isn’t ground tying because you’ve scolded him in the past for moving, he’s staying put because he knows his job is to stay with you. If you’ll excuse an over-used COVID phrase, the horse knows, “we’re in this together.”

He doesn’t jump down the steep embankment of a creek because you forced him to, but because he sees the horse below in trouble and knows we must help. He doesn’t question when you ride away from the herd, because he knows there must be something important to do ahead. When a horse begins to understand his job, not just giving rote responses, he begins morphing into the exceptional category.

Work ethic is one of the most important qualities to instill in a young horse. It will be much harder to teach when the horse is older. It starts early with groundwork and is one of the very first things a riding horse learns—keep going until I tell you to stop. One of the most fundamental tenets of classical horsemanship (wisdom which dates back 5,000 years), is that forward motion is the basis of all training. Without free and willing forward motion, a horse cannot be trained. No truer words were ever spoken.

When taught early, consistently reinforced, and significantly rewarded (with release, praise and rest), even a horse that is by nature lazy, will develop a strong work ethic. Some horses have a go-for-it temperament too—game for any adventure, always looking ahead, eager to prove themselves. When you combine this kind of temperament with a good work ethic and solid training, you are well on your way to exceptional.

Behind the Magic Curtain

Horses are extremely fast learning animals who are willing and seek acceptance by nature. Sometimes truly exceptional horses can be made from the most unlikely candidates. You can turn a Scarecrow into Braveheart, by simply shaping their behavior. A subordinate, omega horse can develop into the best lead horse and become a steady partner.

For instance, all horses are instinctively flighty and fearful, some more than others. But we can systematically teach any horse how to deal with its fear in a different way. By replacing one behavior with another, we can turn fear into curiosity. By praising and rewarding investigative behavior, we can instill bravery. I have written and talked a lot about “de-spooking” horses (if only there really were such a thing); check out my blog and podcast for more information on this training technique.

At the very core of a horse’s behavior, he is drawn to the herd for comfort and safety. No matter what his circumstance, a horse will always seek acceptance into a herd. To me, this is a quality we can shape to our advantage. What a horse gets from the herd is a sense of safety, structure (rules), and leadership (someone to take care of you and tell you what to do). Horses are also comfort-seeking animals and the herd provides them with plenty of that in the form of social engagement, friendship, mutual grooming, napping and frolicking.

When a horse feels alone, he will always seek out a herd. From the first moments of interacting with a horse, young or old, it’s my goal to teach the horse to seek acceptance from my herd. To show him that I will be a strong, but fair, leader, and that I will always watch out for his safety—and never ask him to do something he’s not capable of. He will learn to trust that I will have high expectations of his behavior, but that I will also recognize and reward his efforts. In short order, he is seeking my acceptance and getting the same good feelings from me that he gets from the herd. Ultimately, he is willing to leave his herd and go anywhere with me.

To me, there are few things in life as satisfying as riding a great horse in the wilderness. To have an exceptional trail horse—one that trusts you, is safe, reliable, willing, loyal, and dedicated to the task at hand—is a thrill that few people get to experience. I’ve been fortunate to ride a few great trail horses throughout my career, and I’ve got at least one more in the making.

Not every horse is destined for greatness. Not every great horse was naturally talented to begin with. And every horse has the potential to be great in the right hands. In the end, it takes a lot of hard work, patience, dedication, and determination. But to me—without question—a great trail is made, not born.