Assessing your tack—in terms of its condition, fit to the horse, and appropriateness for the horse’s discipline and level of training—should be ongoing, but doing a thorough assessment should happen at least once a year. For me, New Year’s Day is the time I like to plunge into my horse’s saddle fit, consider what goals I have for the upcoming riding season, and plan for any changes I may need to make.

My Quarter Horse mare, Annie, is going to be 15 years old in 2022. It’s a big leap away from prime time, landing her squarely in middle age (and there’s no need to discuss the middle-aged spread we all experience). Let’s just say that with every year of a horse’s life, its body undergoes significant changes.

This year, my evaluation of Annie’s saddle fit revealed that it’s time for me to make some major changes.

Annie is small, very short-coupled, and round as a 55-gallon barrel. At 14.0 hands, she’s the perfect size for me, and being short-backed and quick-footed makes her super-fun to ride. Even though Annie is round, she’s still a very little horse—a pony, really. She’s also quite short from withers to loins, presenting additional challenges with a Western saddle. Low withers, short-backed, small stature, round barrel—these are the challenges I face in finding the best saddle fit for her.

Because her withers are not prominent and her physique is rotund, her saddle is always prone to slipping—no matter how tight the girth. This has been her nemesis since she was a youngster, and she’s grown quite weary of being cinched up tight.

In the past few months, I’ve seen increasing resistance from her when I am saddling. I can tell she dreads it. She bows her back, steps backwards, and makes sour faces, which make her opinions quite clear. These changes in her behavior made me suspicious, so I scheduled my vet for a thorough examination of her back. Dr. Casey Potter is a performance horse and lameness specialist, who treats world champion horses for lameness and structural unsoundness—including the spine.

I was tremendously relieved when Dr. Potter found no signs of soreness or abnormalities in Annie’s back, giving me confidence that her spine is strong and healthy. Still, I knew that my saddle fit needed improvement, because a tight girth was clearly creating her discomfort. She was telling me she had reached her limit, and resentment was building.

My first step was to re-evaluate her saddle fit, starting from scratch. First, I set the saddle on her back without a pad or cinch and pressing down from the top, I slipped my fingers under the bars of the tree, running them down her back from front to rear, feeling the amount of contact the bars of the tree had with her back. As I suspected, the bars were not making even contact down the length of her back and it was bridging, causing pressure in the front and rear, but not in the middle.

My next step was to try various small bridging pads that are designed to adjust for the contours of the horse’s back that cause the bars of the saddle tree to bridge. I’ve been using a shim pad on Annie for years, to mitigate asymmetry and bridging, but it was beginning to look like that wasn’t sufficient anymore. The short shoulder pad seemed like the right shape for her back, but it was too big for her compact frame.

"Bridge the Gap" with Bridge Pads by Circle Y

Whether a horse is short-backed, long-backed, hip high, sway backed, thin of flesh or prominent of withers, it can affect saddle fit. Depending on the length and shape of the horse’s back, the bridge pad, shoulder bridge pad, or long shoulder bridge pad may help improve saddle fit.

Throughout this process, it became increasingly apparent to me that the fit problem was less about the shape of her back and more about the length of my full-skirted Western saddle. That’s not an easy pill to swallow when I have a tack room full of fabulous saddles, but improving Annie’s saddle fit means buying a different saddle. My full-skirted Monarch with a 16” seat is simply too long for her short pony-type build, and the bridging is related more to the saddle length than any dip in her back.

The Wind River saddle, of all the saddles I designed, is for just this sort of situation. It’s got the eye-appeal of a classic Western saddle, the same close-contact, comfort features, and functionality of the Monarch, but with a rounded skirt that significantly shortens the overall length of the saddle to 27 inches. Conveniently, I am of small stature, too, so I’ll order a 15 ½” seat (which is big enough for me) to help shorten it even more.

I guess both Annie and I will be getting a late Christmas present this year! Like many things in the supply chain these days, saddles are in high demand and low supply, so I know I need to order now, to enjoy my new saddle this summer. This saddle comes in three colors, but personally I prefer the natural oil over walnut and black, because it eventually turns to a beautiful mahogany patina, which accentuates Annie’s deep red color.

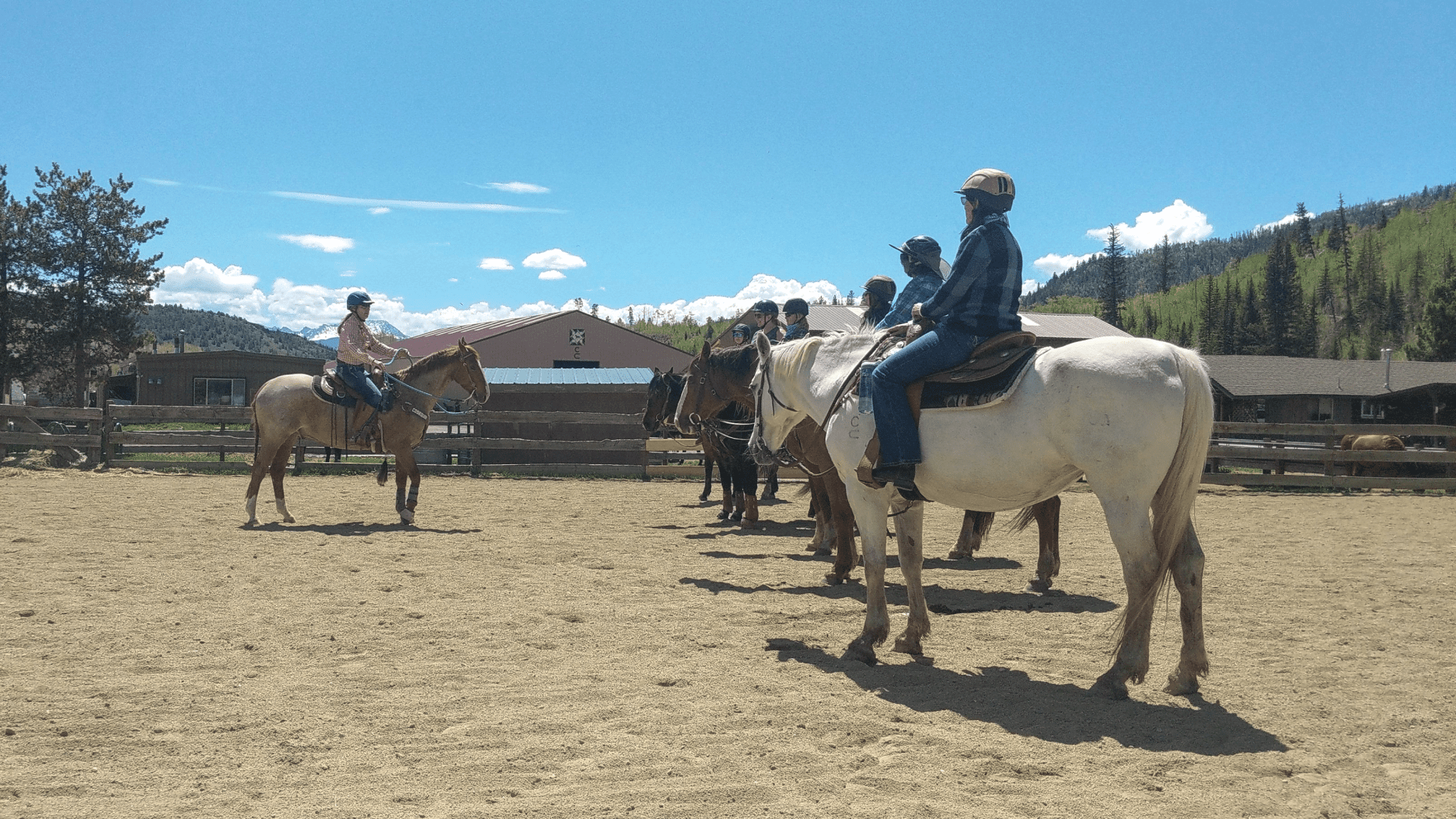

New Year’s is also the time of year I like to plan for the upcoming riding and training season—while there’s plenty of time to get organized, leg-up my horse, and invigorate my training plans. This year, my husband and I have an ambitious schedule of clinics and versatile ranch horse competitions we want to attend.

Although my role will be more as a groom and coach rather than as a competitor, I still need my little mare to be fit, happy and comfortable in her tack. Far better to bite the bullet now so I have time to order the saddle, get it fitted, and for her to get comfortable in the new saddle before the busy riding season begins.

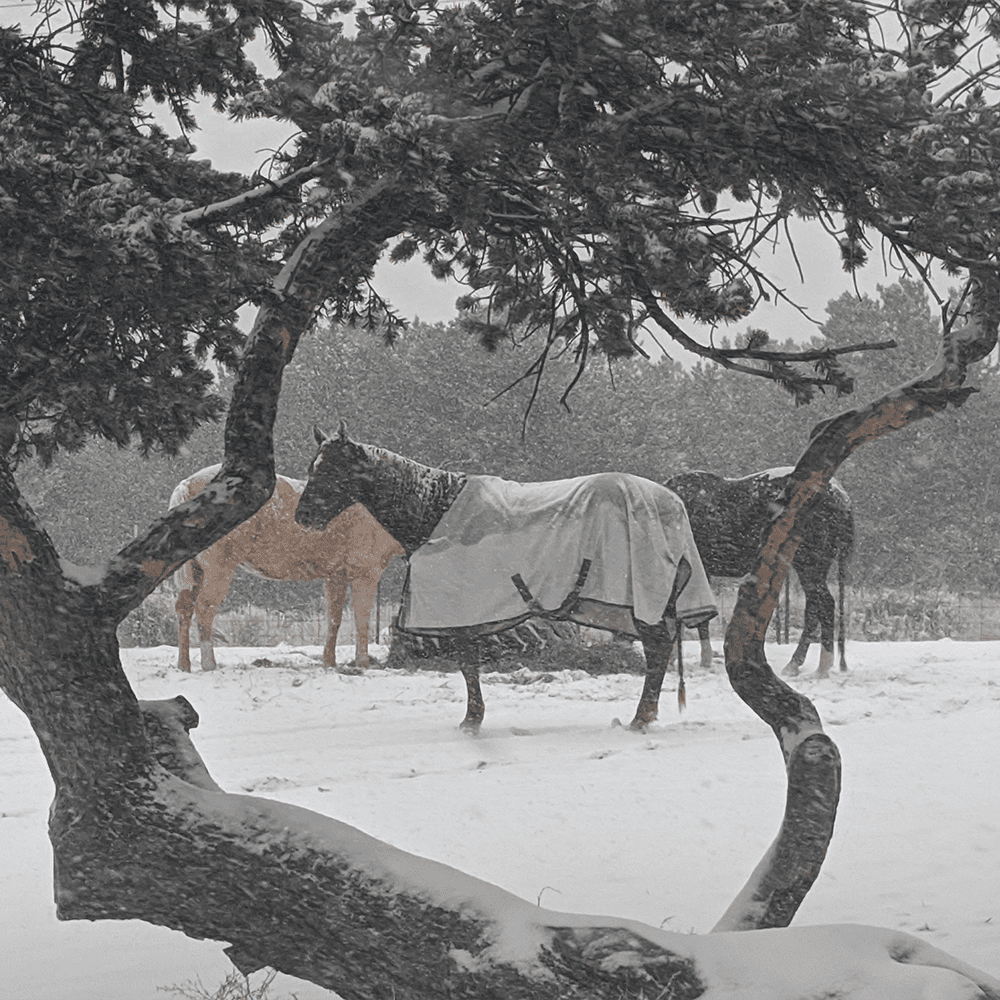

In the meantime, the snow and cold has driven us indoors to ride, and since I am without a well-fitted saddle, I’ve decided to focus on riding bareback until my new saddle comes. Surprisingly, riding in the bareback pad also gives me the opportunity to train the habitual cinchiness out of Annie. Even though the bareback pad girth is soft and never pulled tight, she’s still resistant when I go through the tightening motions—more evidence that it’s an ingrained habit and not a true reaction to pain.

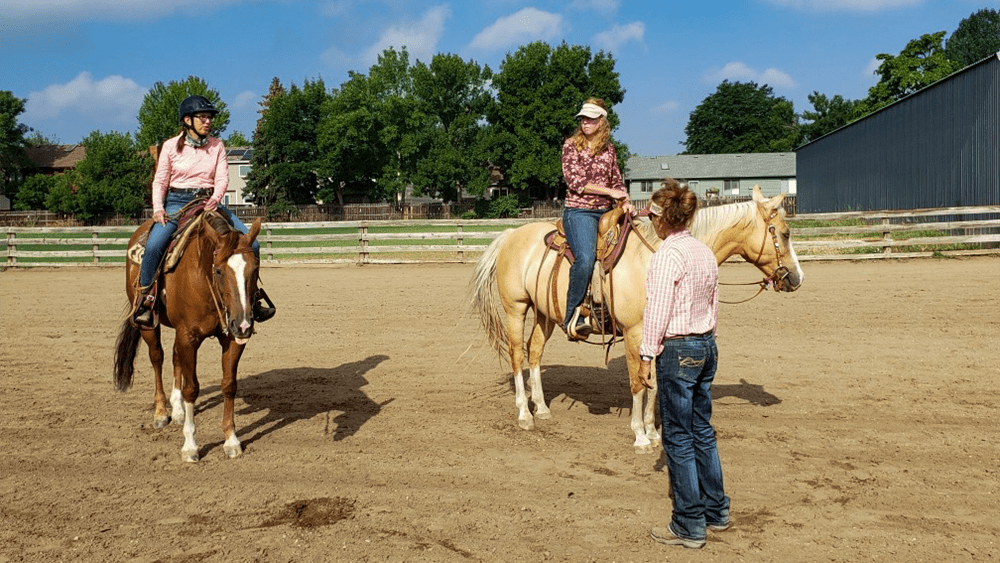

As I slowly snug the soft girth of the bareback pad, if she tenses and bows her back up, I gently send her forward in a circle around me, one way then the other, waiting for her to relax. After just a few days, already one behavior is replacing the other and when she begins to tense, she then relaxes and steps forward. By taking the time to work through her resentment now, by the time my new saddle comes, I’m hopeful this habit will be long gone.

Of course, riding bareback will also help my riding skills. Honing my balance, building core strength, and increasing my endurance are just a few of the benefits of riding bareback, and these are all essential to staying strong as a rider, particularly as I age. It helps me stay in better riding shape from using my abdominal and leg muscles more, and most importantly, it hones my balance on the horse. Remember, balance naturally deteriorates as we age, so riding bareback is a good way to combat aging!

On some days, I shed the bridle and ride Annie bareback and without the bridle, with just a neck rope. This brings a refined subtleness to my riding and cueing that seems like pure connectivity. It’s harder work for the horse without the bridle, since she must pay rapt attention to my cues so as not to miss something. But it brings us both together and makes our shared language more fluent.

Now that I’ve bitten the bullet and made the decision to buy a new saddle for Annie, I’m excited about it and I can’t wait to try it out. I’m working on my patience too, since it will be a couple months before my new saddle arrives. In the meantime, riding bareback makes my indoor arena seem much bigger than it really is, and I’m confident that I am improving my stamina and balance.

Despite all the odds, this year is off to a great start for me. Now is the time to make your plans for next summer and to evaluate where you are now with your horse, and where you hope to be this time next year. I wish you all the best for a bright, healthy, and happy new year!