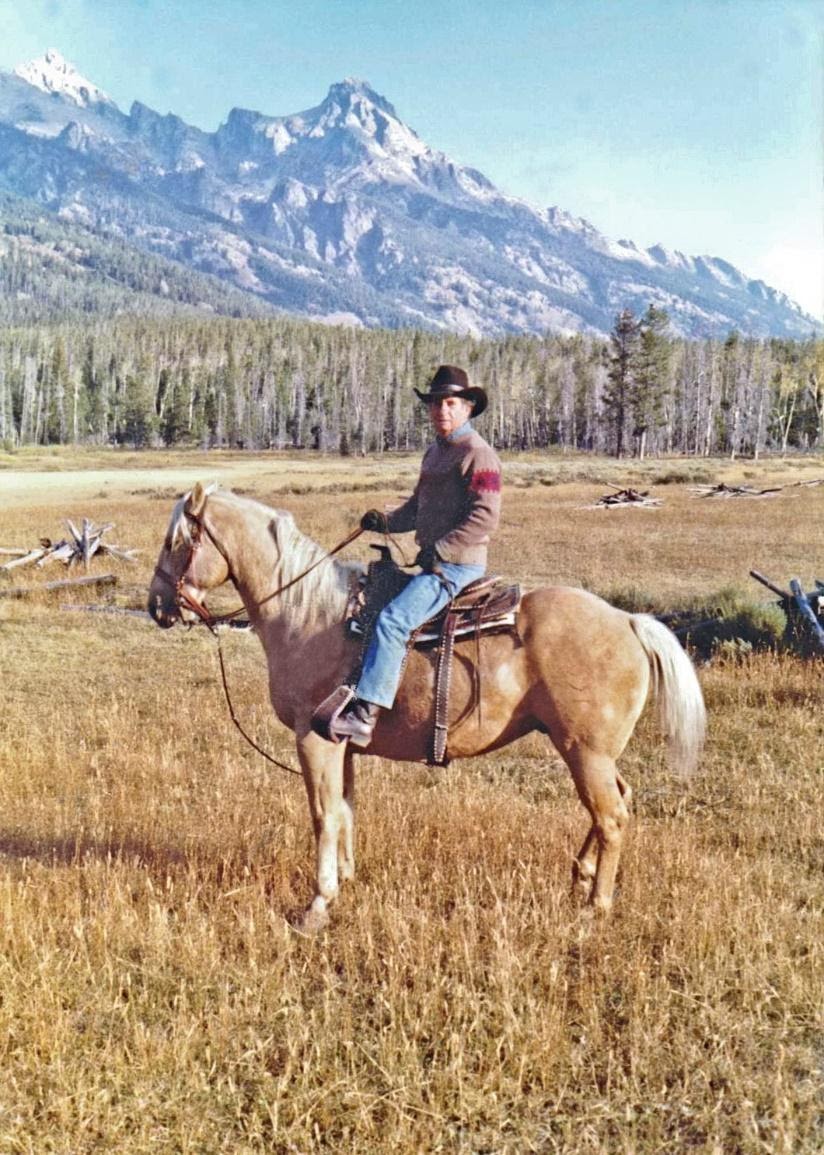

Photo © Whole Picture, Whole-Picture.com

“Try That One More Time.” When it comes to horses, these words are often looked back on with regret. They’re often the words muttered right before something goes terribly wrong. Words matter. Sometimes we need to listen to the words that come out of our mouth and to listen to the voice inside instead.

I strongly believe that most incidents with horses are entirely preventable and if we consider an incident to be an opportunity to learn, not a failure, then we get safer and more effective with horses as times goes on. If you think about incidents as “freak accidents,” you’ve lost the opportunity to learn, grow and improve. There’s always a cause and effect; there’s always an opportunity to learn and grow as a horse person. Recently, I had a message from a rider that was sadly an all-too-familiar refrain. Here’s what the message said:

I had been riding seven months and was posting while trotting and doing 20-meter circles and reverses. We had ridden over an hour. It all clicked that day. I ended with a canter. The trainer wanted me to canter one last time. My intuition said no. I told myself to just do what she said. As we are cantering she (the trainer) is yelling use the crop, use the crop. [The horse] got scared, did a 360 and went into a full run. I hung onto the mane with one hand as she instructed then finally I fell. I couldn’t move. [The trainer] tried to pull me up. I told her not to. She assured me I was ok and the breath was just knocked out of me. I finally was able to get up in searing pain. She had me get back on and post and trot. I did, like a fool. All bent over, I untacked, put him up, drove home two hours. My husband rushed me to the ER. I had broken T-12, crushed L-1, fractured my whole vertebrae and had a concussion. I was told I missed paralysis by 1/8 inch. For three months I couldn’t lift more than the weight of a coffee cup. Riding brought me so much peace and joy –before this incident.

There are quite a few lessons to be learned here. Falling off is part of the sport and can only be entirely avoided by not riding, but while it’s a rough and tumble sport, I do not believe serious injury has to be a part of it. If we learn to not push the limits of our horses and our own abilities, if we learn to pay attention to that inner voice that often warns us when things aren’t quite right and if we let go of archaic and egotistical approaches, the risk goes way down.

Words Matter

I’ve seen many horse wrecks that started with the words, “Let’s try that one more time…” In several decades of work with the Certified Horsemanship Association (CHA), a nonprofit organization dedicated to safe horsemanship instruction, I’ve learned these words to be a red-flag warning. What those words really mean is, “Even though I think we’ve already done this enough, and even though I think there’s a chance we’ve already accomplished what we needed to, let’s get greedy and do it one more time.” When it comes to horses, this kind of approach often backfires.

I’ve learned this important lesson myself over the years and I can think of more than one instance where ‘trying it one more time’ was the worst possible choice and resulted in a wreck and/or an injury to a horse or a rider. When we say things like, “one more time,” or “I’ll try,” or “maybe we should,” there is an unstated concern that something might not go right. When you hear words like that, why not complete the thought and consider why you need to do it again, what good can come of it, why do you think you might not be able to do it and why are you not sure of what the right thing to do is? Maybe just stepping back for a moment and reconsidering isn’t such a bad idea.

When you let words of doubt creep into your vocabulary, like “I’ll try,” it really means you don’t think you can do it. You are doubting yourself and giving yourself an escape. The problem is that horses respond to your level of confidence and determination, be it high or low. When you use words like “if” and “try,” you erode your own confidence and your horse may respond negatively as well—by challenging your authority or losing his own confidence. When you feel the need to use doubtful words like try, if, or maybe, just take a moment to consider why you feel that way. Is this a smart thing to be doing? Are you prepared and qualified to do it? And what good can come of this or what can go wrong? If the answers are affirmative, go for it and drop the ‘try.’ I AM going to do this! If any of the answers are less than affirmative, maybe rethinking or thinking it through, is not a bad idea.

Trust Your Inner Voice

When people are describing bad incidents with their horse, I often hear them say, “I knew I shouldn’t have done it, but my trainer/spouse/friend pushed me, so I did.” Our inner voice of wisdom is important and although it may not always be right, it’s worth at least considering. Far too often in hindsight, it seems clear that had you listened to that inner voice, the wreck may not have happened.

It’s important to hear, respect and consider your inner voice and to take responsibility for your own self—don’t abdicate that responsibility to anyone. Don’t let others pressure you into actions that you don’t feel good about. You know yourself and your horse better than anyone. You know your capabilities and you know where you are emotionally in that moment better than anyone. Yes, sometimes it’s helpful to have someone to gently push you into things you aren’t entirely comfortable with, but no one has the right to pressure and cajole you onto something you are not prepared for.

If you have realistic goals and an objective view of both your and your horse’s capabilities, then you should be confident in your own decisions and not let yourself cave into the pressure of others. Remember, your trainer works for you, not the other way around. Make your expectations and needs known and don’t be afraid to stop, look and listen when you hear that inner voice of warning.

Let Go of Archaic Notions

The idea of getting back on the horse that just bucked you off, is rarely a good idea, in my opinion. Whether you got bucked off or just fell off, chances are you are not in the best frame of mind to get back on that horse. Chances are also good that your horse is not in the best frame of mind either—he’s probably scared or anxious and something led to the problem to begin with. The adrenalin rush that comes from this kind of incident can often mask injuries that you may have sustained and getting back on may make the injuries worse.

When a rider comes off the horse, we’ll call it an “unscheduled dismount,” I prefer that she take a break, sit down and rest, get checked out medically if needed, get control of her emotions, debrief the incident, and only think about getting back on when ready. Maybe that’s today; maybe not. Often, I’ll get up on the horse after an incident, to settle it and let the rider see what’s going on. If the rider feels strongly about getting back on, that’s fine and I will support her as best I can. But no one else has the right to tell you to get back on. Not your husband, not your friend and not your trainer.

Again, take responsibility for yourself and don’t let yourself be pressured by others at times like this. Before getting back on a horse after an incident, think it through. What good will come of this? What would have prevented the incident from happening? Is my horse injured, physically or emotionally? What needs to change with my horse or with my own skills or equipment, to prevent this from happening again? Taking a little break—rather that is for an hour, a day, a week or longer, is not necessarily a bad idea. Think through what happened, how you may have prevented it, and what you would’ve done differently if you could. Armed with this kind of knowledge, you will come back to riding with more confidence and a plan to not let that happen again. Always give yourself time to heal—both physically and emotionally, after any kind of scary incident with a horse.

The sport of riding is a challenging and exhilarating sport that comes with a certain amount of risk that cannot be entirely eliminated. But we don’t need to add to that possibility by doing foolish things and taking unnecessary risks. This is a sport that takes years and decades to master and getting in a hurry and cutting corners rarely pays off. The same thing is true of training horses—generally the slower you go, the better the outcome.

Be patient in developing your skills and your horse’s training. Work with trainers that are supportive of your needs, listen to what you have to say and make good decisions. Learn to trust your inner voice and hear what it has to say. Let your rational mind be the judge of whether or not that inner voice has a point; don’t let someone else make that judgment for you. And finally, when a rider comes off a horse, take the safest and smartest approach—get medical clearance, take a break, debrief the incident and make a smart plan to get back in the saddle safely.

And don’t forget to enjoy the ride!

Julie Goodnight