I had an interesting question recently from one of my Facebook friends: “If you want to stay on, at what moment does the rider decide to execute an “emergency dismount?”

This is a good question and one to which there is no definitive answer, except, “it all depends on the circumstance.” In general you are usually better off and safer staying on the horse if it is at all possible. Even teaching the emergency dismount is somewhat controversial for two reasons. First, practicing the emergency dismount is risky and injury-prone; when vaulting off a moving horse, it’s easy to fall down, sprain an ankle or worse. So practicing something that you may or may not ever need but may cause injury just by practicing is questionable. Of course, you could certainly argue the opposite that if you were to ever need it, having practiced it may make you less prone to injury. When I taught kids, I had them learn and practice the emergency dismount routinely. Now that my student base is middle-aged and older adults, I don’t teach it at all—because of the potential for injury in the practice.

The second reason why it is controversial to teach the emergency dismount is because you may end up with a rider that bails off the horse for no good reason when they should have stayed on and this can cause a lot of problems. Again, you are usually safer on the horse than off, because once you come off you are probably going to hit the ground (or some other hard object) and you may become a victim of the horse’s hooves. However, like everything with horses, there are exceptions to the rule.

In my entire riding career, I have only voluntarily come off a horse a few times. I have certainly had plenty of “unscheduled dismounts” through the years, but those weren’t by choice. Most of the time I have come off a horse, I have realized that I couldn’t stay on because I was too out of position or out of balance and I came off knowingly but not exactly executing an emergency dismount—more like being ejected. It’s funny how time seems to be suspended in those moments and usually there is time to think about the fact you are going to come off and how and where you might land, but not enough time to execute an emergency dismount.

The few times I have voluntarily done an emergency dismount, there have been some extenuating circumstances, and these are probably the only situations in which I would do it. In both instances I can remember, the horse was running away with me, out in the open—not in an arena– maybe bucking maybe not, but I had already tried my best to regain control and I determined I couldn’t do it. Running away, in and of itself, is not enough to make me bail because the one thing about a runaway horse, which I learned riding race horses, is that eventually he will run out of oxygen and stop. In both cases that I did bail, the horse was headed for something dangerous, like a barb-wire fence, with seemingly no concern about his own well-being. Running away is one thing, but when the horse is in such a panic that it loses its sense of self-preservation, you’re in trouble. And BTW—this is a good thing to remember—when the horse is willing to cause injury to himself, he is way beyond rational control and both of you are at great risk.

There are probably a few circumstances where in hind-sight I should have bailed off but didn’t. But my tendency is to stay on board if at all possible. I think that if a rider is too quick to bail off, not only is she risking injury in the dismount but there will also be times when she would’ve stayed on if she had tried. But a controlled crash-landing is usually better than an uncontrolled one. I do think there is some value in learning how to take a fall—tuck and roll. And I think it is valuable to know the process of an emergency dismount.

There are two really critical factors when you are coming off a horse– whether it’s an emergency dismount or not. First, you have to get your feet clear of the stirrups ASAP. You’d be surprised how many people, in a panic, go to dismount and forget to take their feet out. The potential disastrous results are obvious. Secondly, DO NOT hold onto the reins—let the horse go! You’d be surprised how many people try to hang onto the reins when they fall, in a last-ditch effort to maintain control, and then end up pulling the horse down onto them or breaking an arm or dislocating a shoulder. If you are coming off a horse, voluntarily or not, get your feet out of the stirrups and let go, pushing yourself as far away from the horse as possible.

It is an unfortunate characteristic of the sport that things sometimes do not go according to plan. And even with the most docile, steady horse, there may be times when bad things happen. Keeping your wits about you and continuing to think through the crisis are the most useful tools you have. The emergency dismount has its time and place, but it should be a method of last resort.

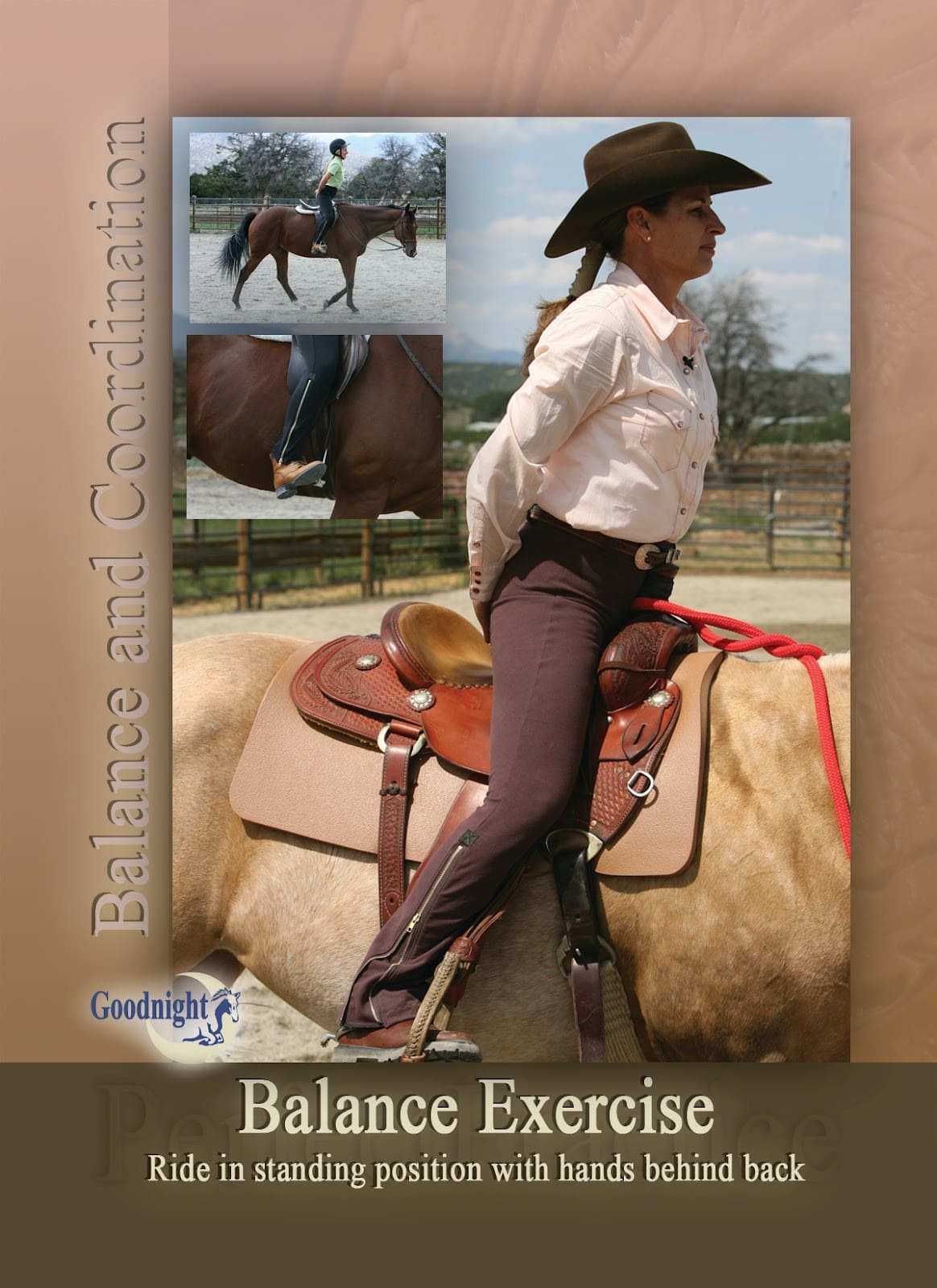

Teaching the Emergency Dismount

Learn the skill with my video at the Certified Horsemanship Association’s video page: http://www.youtube.com/chainstructor. On rare occasions, you may need to dismount your horse unexpectedly. In almost all instances, it’s better to stay on your horse rather than jump off. However, this is a good skill to know.

First and most importantly, kick your feet out of the stirrups. Then place your hands on the saddle’s pommel to protect your stomach from the horn. Then kick your right leg high and up over the saddle’s cantle—careful not to hit the back of the horse. Be sure to land facing forward with your knees bent so that you’re prepared to move away from the horse as necessary.

Make sure not to hold onto the reins. Holding on can cause you to pull the horse on top of you. If you need to get away, let go of the reins and get away at the same time.

Here’s to hoping you always stay on the topside! Come visit the blog and let me know how you’ve used your knowledge of the emergency dismount.

Julie

Until next time,

–Julie Goodnight