Top trainer Julie Goodnight helps you analyze your riding posture and prepare you for the perfect canter. Find out how rider errors contribute to wrong leads and more.

By Julie Goodnight with Heidi Melocco

Cantering is the topic of choice at many of my clinics. Riders want to know how to ride the complex gait with confidence and what they can do to canter more easily. I often hear “my horse will never pick up the right lead,” “what can I do to stop this horrible fast trot that comes before my horse will canter,” and “my horse won’t keep cantering once we get the gait.” These are my top three cantering complaints and the easiest problems to fix—with a little bit of rider awareness, a new plan to make cantering cues clear, and an attitude shift to help riders know that they are in charge and can expect their horses to do what was asked.

When a horse is well trained and has cantered many miles in the past, I believe that ninety-nine percent of canter concerns are rider induced—there’s always something the rider can do to make their ride better and to help their horse know exactly what they expect. Here, I’ll help you understand how your body position, tension and timing may be telling your horse something different than you think. You’ll have the tips and tools you need to step into the canter with a clear cue and knowing that you’re sequencing your cues so that your horse can easily understand your requests.

Cantering Leads

Why does the lead matter? It’s difficult for the horse to balance himself if you ride around a corner. If your horse is following your exact cue, he should take the lead that you ask for—not just start cantering and choose a lead himself. Plus, for competition, there’s often a required lead depending on the direction you’re tracking or according to the pattern. All that said, if you’re riding straight down the trail or the middle of the arena, there is no correct lead to take. But to be a better horseman, it’s best to know what you’re asking your horse to do.

When riders come to clinics and they want to work on leads, I first ask if the horse takes the wrong lead when traveling both directions. If the horse misses his leads in both directions, there’s most likely a cueing problem. The horse isn’t clear about what lead you want him to take and he isn’t set up to take the correct lead.

What goes wrong with a cue? Many riders can’t state what they do to cue for the canter. Because you have to cue for a specific gait and cue for a lead, there are lots of variations in cues and there’s lots of confusion.

The horse pushes off into the canter with the outside hind leg. If you’re asking for the right lead, the horse first pushes off with the left hind (and vice versa).

Use your outside leg to reach back a few inches and apply pulsating pressure there with your Achilles tendon. To prep for a right lead, move your left leg back. A well-trained horse will step his hips to the right. This movement is done at the walk or while standing still. I practice this move at the walk in a relaxed and easy frame without thinking about adding speed. You need to be able to reach back and get the horse to yield his haunches. That needs to be a cue to move the haunches and not just a cue to speed up. I like to walk straight down the long side of the arena, reach back, if the horse yields his hip, release him and pet him. Do that over and over until the horse knows that the cue to move his hip. Once your horse can proceed with a canter cue, the horse is now set up for the correct lead. That’s called “haunches in.”

For me, the canter cue is outside leg to move the haunches in, then I lift up and inward with the inside rein to keep the horse from diving in, then the actual cue to canter comes when I curl my hips in the canter motion (which is a move like pushing a swing.) I also like to use a kissing sound. It’s all about the sequence—outside leg, inside rein, push with the seat and kiss. I would guess that 80 percent of people who think their horse has a lead problem find that the problem goes away once they clarify their cueing sequence.

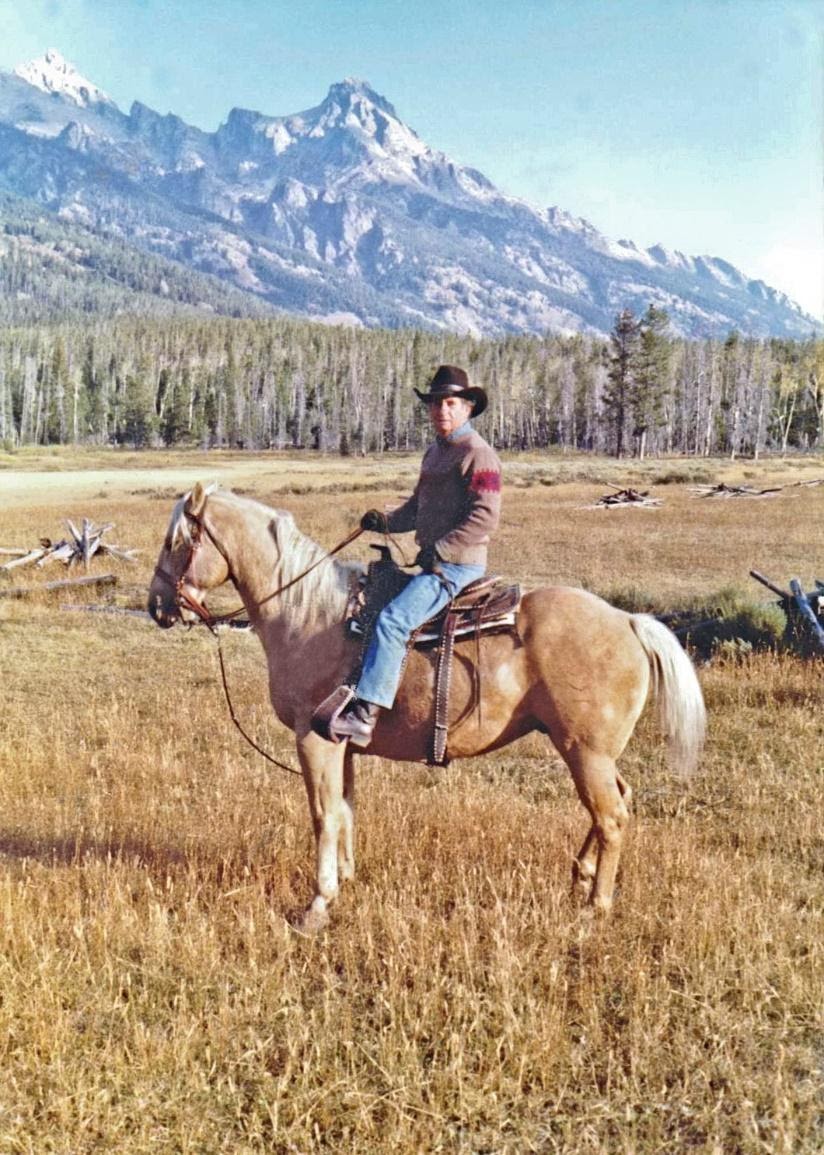

Caption: Practice “haunches in” at the walk and trot so that you know you can control your horse’s hips before adding speed and cueing for the lead at the same time.

If your horse is still having trouble with leads after working on “haunches in,” try cueing your horse right before the turn to the short side of the arena. Make sure to cue before the turn and not during the turn. If your horse enters the turn, he’ll actually turn his hips to the outside and he may take the wrong lead as his hips pop out. This is why circling isn’t a great way to teach a horse to pick up a lead. As you pull your horse into the circle, the horse pulls his hip to the outside, he can’t pick up the correct lead, but if you’re going straight then just start to turn, he’s still moving correctly at that moment.

Caption: Cue your horse for the canter just before you turn to help him place his hips correctly to pick up the correct lead.

If the horse will only take one lead, there’s a chance that there’s a physical issue. This is true especially if your horse usually takes the correct lead and suddenly isn’t so willing. If that’s the case, I want to rule out physical issues and have the horse evaluated by a veterinarian or veterinarian who’s also an equine chiropractor. If it’s an old injury, especially on a hind leg, the horse may have learned to compensate and just isn’t as strong when traveling to one direction.

Trotting into the Canter

Cueing can be the culprit again. If you release the horse from the cue at the wrong time, the horse will learn to do whatever he was doing when he got the release. I typically see two types of horses who become afraid of the canter. If the horse becomes afraid to canter, the rider may be reluctant. The rider picks up on the reins or pulls back at the moment of cueing. Even if the rider is reluctant in their mind, the horse may pick up on that.

Other times it is a cueing issue. If you think you’re cueing for the horse to canter and instead he just trots faster and faster and faster, you’re probably releasing the cue at the wrong time. Compliant and trained horses can learn to take the cue to canter as a cue to trot faster. If the horse mistakes the cue and you start riding a fast trot—by posting or by sitting the trot—you are condoning the trot and telling the horse that he’s doing the right thing. Or, the rider stops the horse because he trotted instead of cantered. Once the horse gets a break, he thinks he’s been rewarded and he did the right thing. The horse doesn’t want to canter, he wants to work as little as possible.

If the horse mistakes your cue, make sure that you have a clear cue. If you’re confident of your cue sequence and your horse still trots faster, let him know that isn’t what you’re asking for. Stop him abruptly and immediately recue him for the canter. If he does it again, abruptly slow him down with a stop cue using your seat and reins then immediately ask again. Make sure not to give him a break and keep applying the pressure of the whole cueing process until he gives you the right answer and starts to canter. This is the same training sequence you’d use if you want to alleviate the trot or even a step taken before the horse begins to canter—to teach the stop to canter or walk to canter.

Caption: This young horse had not cantered often and thought a cue to speed up meant to trot more. Notice that I am sitting deeply and not posting with the trot. Soon, he understood and picked up the canter

Note that when the horse began to canter, my hands are forward and low, in front of the saddle horn. This position lets him know that rein pressure won’t mean too much pressure on his mouth when his head moves down into the canter.

Make sure to praise your horse when he picks up on your new, more precise cues.

Avoiding the canter: The horse’s nose dives down with every stride of the canter as he’s lifting his back and hindquarters and stretches his nose down. This happens especially on the first stride when he moves from no impulsion to full impulsion. If you as a rider don’t actively give a release with your reins, with each stride and at the beginning, the horse hits the bit. If you’re even just tense and don’t relax your hands to help the horse get a release of the reins, you can be adding to the problem. If your horse has a lazy demeanor and hits the bit, he takes that as full permission to stop cantering. If your horse is sensitive and nervous, he may hit that bit and get scared and therefore lose trust in you as a rider.

Whether it’s because of a cueing problem or because the horse has felt the bit in his mouth, the answer is the same. As soon as you step into the canter and with every stride of the gait, you need to reach forward and down (not up, that can still hit the horse in the mouth as your horse’s head goes down). If your horse is reluctant to canter –they actually become afraid to canter and throw their heads in the air and run in a panic. When I’m attempting to break that habit, I over exaggerate and reach farther forward than necessary to show the horse that he can trust me.

If you don’t think you can make an exaggerated change to break this habit with your horse, consider asking a more experienced rider work with your horse to show you how the canter can look and to remind the horse that stepping into the canter doesn’t have to mean getting hit in the mouth. You’ll still have to make an exaggerated change when you’re back in the saddle because he knows the difference between riders. You’ll have to focus on fixing yourself, but you’ll get a boost of confidence to see someone else riding your horse and knowing what your horse can do.

Trotting into the canter can also be a problem if you haven’t cantered your horse for a long period of time. If you haven’t cantered recently, your horse might think that your go faster cue just means trot and trot faster. It will take your horse a few times to understand what you’re asking for and it’s important to cue your horse with precision.

Breaking Gait

Once you’re already cantering, it’s the horse’s job to keep doing what you asked for until you tell him to do something different. He should keep cantering and not choose to slow down on his own. However, horses don’t necessarily want to canter around and carry a rider –it’s hard work! Some horses will look for any mistake by the rider and use it as an excuse to stop.